Perspective of materials design with machine learning

Methods and algorithms for machine learning assisted materials design

Cheng Zeng is grateful to Alfond Post Doc Research Fellowship for supporting the research work at the Roux institute of Northeastern University. Computational simulations are carried out using the Discovery cluster, supported by the Research Computing team at Northeastern University.

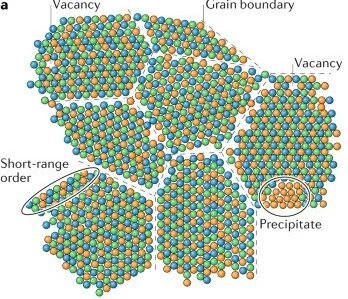

High-entropy alloys, defined as alloys with no less than five elements with almost equiatomic compositions, are emerging materials with superior corrosion resistance, irradiation resistance, strength and catalytic activity. The complexity of defect structure is shown in the below figure. However, design of high-entropy alloys is challenging as many factors should be considered such as compositions, configuration, defect structures and processing of those materials. Thanks to the advance of computer hardware and algorithms, the past decade has witnessed success of ML enabled discovery of high-entropy alloys. Purposes of machine learning high-entropy alloys include prediction, knowledge mining and optimization. Machine learning methods used for high-entropy alloys can essentially be grouped into three categories. Each category, its current state-of-the-art implementation and future challenges are outlined below.

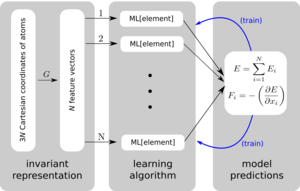

The mainstream is machine learning inter-atomic potentials (MLIP) that aim to fit inter-atomic interactions based on first-principles data. The fitted machine leaning models can accelerate atomistic simulations by orders of magnitude compared to first-principles calculations. This category belongs to the forward design with machine leaning models. Schematic of typical finite-ranged machine learning potentials is depicted in the below figure. Atomic positions are first transformed to features via representations invariant to rotation, translation and reflection. Each atom has its own feature vector to describe the atom interacting with its neighbors. Atomic energies are approximated by machine learning algorithms, which in the end are summed to yield the total energy. The training iterates by minimizing the energy (and forces) differences between machine learning models and ab initio calculations. Since high-entropy materials live in high-dimensional configuration space, a large amount of training data and features are needed. In addition, current MLIPs mostly use element-specific descriptors which significantly limit the transferability of MLIP when predicting materials comprising elements not existent in the training structures. Besides, the MLIPs only perform well in regions where training data are sufficient, necessitating effective sampling of informative structures. Future research directions in this line include develop a universal element-agnostic representation of atomic structures, robust machine learning architecture for inter-atomic interactions and efficient sampling methods.

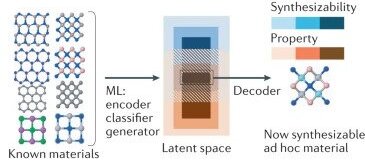

The second category features generative models for inverse materials design. The basic idea of generative models is to learn a probabilistic mapping between continuous latent space variables and materials properties. A typical generative model uses variational autoencoder where inputs are projected to a low dimensional space by an encoder and then a decoder maps the latent space back to the same inputs. Nevertheless, general models often suffer from the overfitting issue, leading to a high failure rate when predicted materials are validated through first-principles calculations or experiments. Generative models also strongly depend on massive data, in particular for complex materials like high-entropy alloys. In addition, the inverse of materials from atomic representation is very challenging because the mapping between configuration space and latent space is not invertible for most machine learning methods. As a result, Incorporation of uncertainty quantification and active learning is required to balance the exploitation and exploration of inverse materials design using generative models. Future development of data-efficient and interpretable algorithms are needed to unleash the full potential of generative methods. Future advance in invertible representation is necessary to expand use cases of generative models.

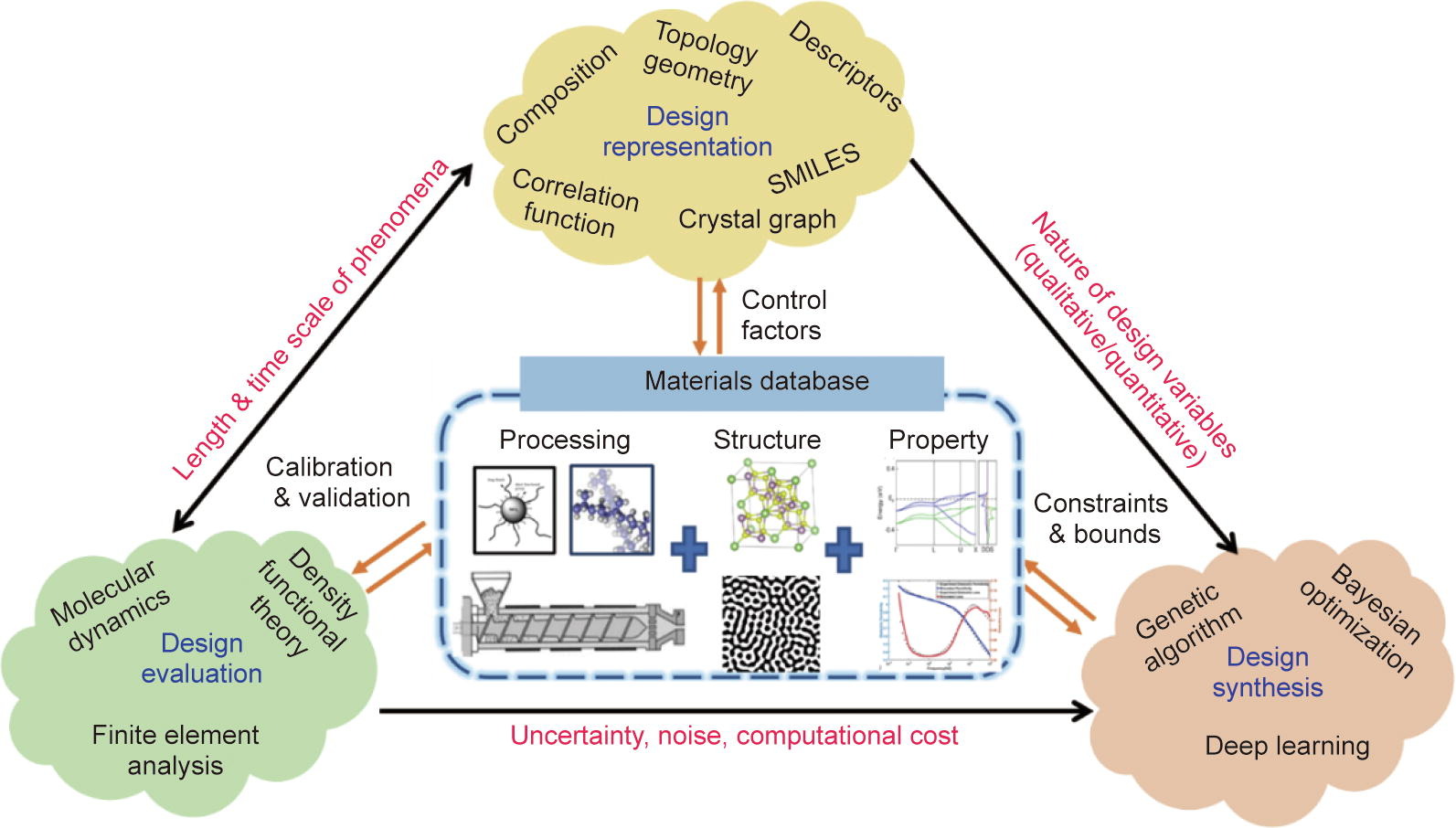

The last category represents machine learning models based on experimental data. This usually takes input as chemical compositions and output as materials properties. The machine learning models can be generic machine learning models (e.g. random forest classifier) for property prediction. Alternatively, generative models can be built for inverse materials design or materials optimization. The issue with this machine learning method is rooted in the quality of experimental data. It is of central importance to ensure the compiled data follow the FAIR principle because of the “Garbage in, Garbage out” principle. More generally, all the data used in materials design loop (see the below figure) should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. For materials dataset, it is crucial to examine the processing conditions of how materials are made, especially for high-entropy alloys which can be manufactured either via conventional arc melting and casting or through additive manufacturing with high cooling rates. Moreover, the curation of new data should strictly follow the data principle as well. Collective efforts are needed among the materials researcher community to safeguard the data quality. Researchers who collect the data should take the caution of data provenance and data governance. Design algorithms that are resistant to data noise are also promising future directions.